This article explores some of the challenges, learning, reflections and opportunities involved in collaborating with grassroots artist collectives in conflict-affected places in academic research settings. Using as a case study the collaborative co-production of the animated short film ‘Colombia’s Broken Peace’, Sara Wong of Positive Negatives re-frames notions of ‘impact’ and ‘capacity building’ in conflict research from often unidirectional conceptualisations (i.e. skills and knowledge flowing from the ‘Global North’ to the ‘Global South’), to a more complex picture of mutual learning and knowledge exchange.

Crop substitution challenges in environmentally protected areas in Colombia

María Alejandra Vélez and María Juliana Rubiano-Lizarazo

In 2020, 48% of illicit crops in Colombia were in special management zones (SMZ) or areas that are important for forest and biodiversity conservation: 20% in forest reserves, 4% in national protected areas, 8% in indigenous reserves or resguardos, and 15.5% in Afro-Colombian collective lands (UNODC, 2021). Although academic literature has shown that coca crops are not the main direct driver of deforestation in Colombia (Erasso & Vélez, 2020; Brombacher, Garzón & Vélez, 2021), coca crops are expanding in strategic environmental and conservation areas. This is problematic for illicit crop substitution efforts. Yet the design and implementation of the government’s National Illicit Crops Substitution Programme (PNIS) has given little consideration to a differential approach, in ethnic or environmental terms.

PNIS implementation started in 2017, as part of the Peace Agreement between the Colombian State and former guerrilla FARC, but it was not until 2019-2020 that there were guidelines for implementation in national protected areas and forest reserves. These guidelines include recommendations on voluntary and collective conservation or restoration agreements; conservation incentives such as bi-monthly remuneration for agreed restoration and conservation activities; sustainable production systems; and technical assistance for capacity building.

The government has also recently developed guidelines to include ethnic communities in the programme, but these are subject to prior consultation and have not yet been implemented with former programme beneficiaries. As illustrated by our case studies in Putumayo and Guaviare, new guidelines incrementally increased mistrust and conflict as the PNIS did not consider or solve land-use overlap conflicts or land tenure disputes between communities with different ethnic backgrounds before agreements were signed.

Currently, 20% of PNIS households are in SMZ – in national protected areas or forest reserves (7.2%) and Afro-collective territories or indigenous reserves (13.6%). However, in the latter case, these are not necessarily ethnic households, which creates tensions between communities. Beyond environmental concerns, PNIS households are also poor: 56% of households in national protected areas and forest reserves, 51.1% in Afro-collective territories, and 53.4% in indigenous reserves live in multidimensional poverty. Hence, government interventions and PNIS need to consider not only environmental dimensions, but should also include productive alternatives designed to simultaneously conserve sensitive ecosystems and improve quality of life.

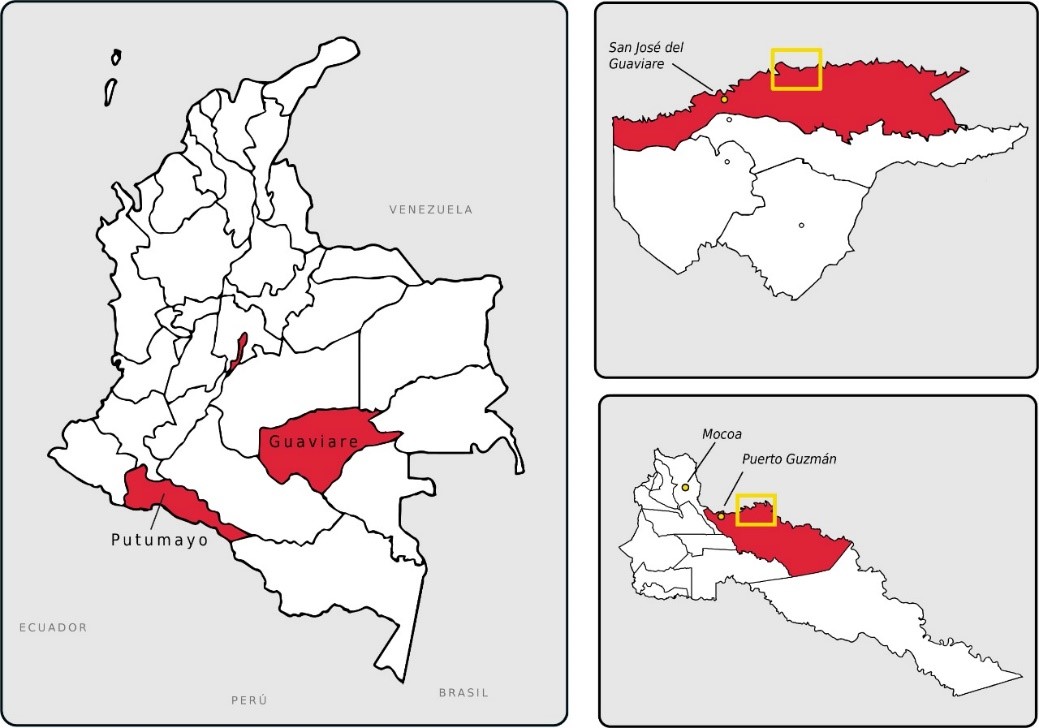

To explore these issues, we are studying the challenges of implementing the PNIS in indigenous or forest reserve areas in Putumayo and Guaviare in the south of Colombia (see Map 1), using social cartography workshops and semi-structured interviews.

From this work we have identified three main challenges for the implementation of crop substitution programmes in SMZs.

Challenge #1: Mestizo peasant coca growers living inside indigenous reserves were suspended from PNIS without warning

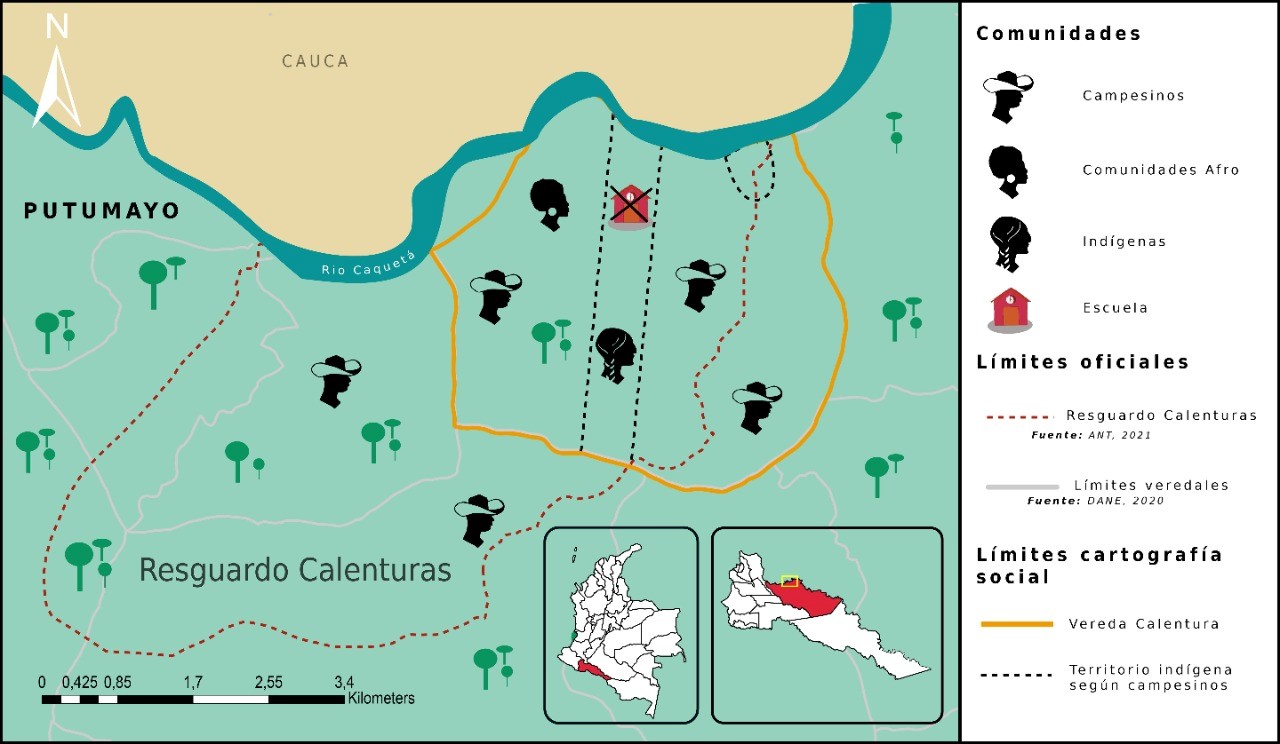

In some cases, peasants signed crop substitution agreements, eradicated coca crops and received immediate food security payments, but before receiving the subsidy to implement a productive project, they were suspended from the PNIS because their plots of land were located within an indigenous reserve (see maps 2 and 3). In other cases, local indigenous authorities didn’t allow peasants living on their collective land to become involved with the programme. In either case, to remain in the programme and receive benefits, peasants had to rent a plot of land outside the indigenous reserve. Despite the costs of this (an average rent amounts to approximately 40% of a minimum wage) some peasants rented new land, but even so, never received their payments for productive projects.

PNIS did not solve (or plan to solve) old land conflicts and tensions before signing crop substitution agreements, exacerbating both mistrust of the Colombian government and land use conflicts. In some cases, peasants claim that the delimitation of indigenous reserves and forest reserves did not consider the presence of diverse communities and land uses. In other cases, peasants do not recognize the presence of indigenous people in legally constituted indigenous reserves.

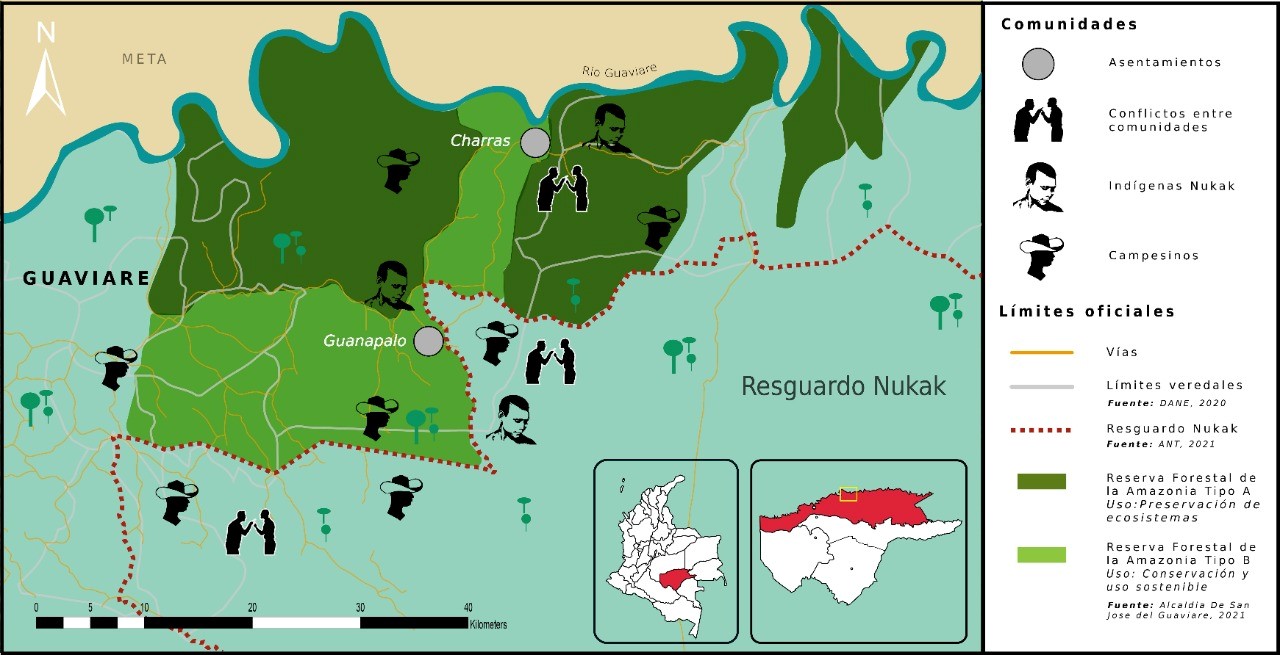

Challenge # 2: Unexpected requirements to remain in the programme for peasants living inside Forest Reserves

Years after peasants signed voluntary agreements to become involved with the PNIS, new requirements to solve land use overlaps with conservation areas were developed. For example, mestizo peasants living in forest reserves, are now required to comply with nature conservation agreements and sign land use rights. However, peasants found this unexpected change in the rules to be unacceptable, claiming that official delimitations of the forest reserve area are not clear (See map 2). With current regulations, peasants in Type A forest reserves (areas with restricted productive uses) must replace their usual activity of cattle ranching with conservation activities, while those living in Type B Forest reserves (areas with more flexible uses) must engage in agro-sustainable cattle ranching. In any other case, peasants need to rent land outside these protected areas. Current regulations also forbid the construction of roads and infrastructure development within forest reserve areas. According to the peasants, in these conditions, cattle ranching is one of the few economic alternatives to coca since no other productive activity is economically profitable with the current roads.

Challenge #3: Differential ethnic approach

Some ethnic communities enrolled in the PNIS have not received any of the benefits due to the absence of a differential ethnic approach. This is the case of Nukak indigenous groups in Guaviare. Forced into new sedentary livelihoods due to displacement by armed conflict and territorial disputes, they have adopted coca harvesting as their main livelihood activity. The implementation of PNIS with a differential approach requires prior consultation with indigenous communities, but it is unclear at what level this prior consultation should occur: settlement, ethnic group or ethnic associations. Other important obstacles – including language barriers, and varying political and social organization within each ethnic group – lead to many unanswered questions. Should substitution agreements be developed collectively or individually? How should technical assistance or productive projects be developed? For example, for Nasa communities in Putumayo, productive projects should be aligned with their own productive calendar and with organic and local seeds, and technical assistance must be provided by trained members of their community.

Future crop substitution programmes in SMZs

These challenges highlight the lack of a structural and comprehensive approach in the design of the PNIS. The initial focus was to eradicate coca and substitute it with another product but without solving underlying land use tensions.

The current substitution programme needs to recover the trust of former beneficiaries by implementing all the promised components. Further, environmental requirements need to be socialized with local communities. In Putumayo and Guaviare, for example, conservation activities are not embedded in the culture of peasant coca growers. In their case, they signed voluntary agreements thinking that they would receive support for cattle ranching. As one peasant put it: “if we grow coca, it’s bad, and now if we work in cattle ranching, that is bad too. What are we supposed to do?” The PNIS needs to provide effective technical assistance to shift preferences for more sustainable activities, while also allowing peasants access to new markets. This implies better institutional coordination with other government organizations in the environmental and agricultural sector to implement programmes in each area, and to develop sustainable alternatives for peasants and ethnic communities. Alternative development programmes need to clarify land property rights and solve land use conflicts as a first step, before signing substitution agreements with communities. The requirements for each SMZ should be designed and socialized at the beginning of the programmes. Otherwise, new interventions can bring more tensions, rather than provide tailor-made solutions for each specific context.

References

Brombacher, D., Garzón, J.C., & Vélez, M.A. (2021). Introduction Special Issue: Environmental Impacts of Illicit Economies. Journal of Illicit Economies and Development, 3(1).

Erasso, C. & Vélez, M.A. (2020). ¿Los cultivos de coca causan deforestación en Colombia? Documento Temático #5. Centro de Estudios sobre Seguridad y Drogas (CESED).

Resolución 056 de 2020. [Dirección de Sustitución de Cultivos de Uso Ilícito]. Por medio de la cual se adopta un documento técnico de soporte para el “desarrollo de los componentes de procesos de sustitución voluntaria de cultivos ilícitos y desarrollo alternativo de hogares beneficiarios que estén ubicados en áreas ambientalmente estratégicas o de importancia ecológica”. October 26, 2020.

Acknowledgements

We thank Lucas Marin and Juan José Quintero for their help in the implementation of the workshops and conducting interviews; and VisoMutop, especially Pedro Arenas, for support on developing the field work of this project.

Credits to Juan José Quintero for all the maps in this blog.

The role of civil society organisations in harm reduction in Northern Shan State, Myanmar

The conflict-affected region of Northern Shan State (NSS) has become the epicentre of Asia’s illegal production of opium/heroin and methamphetamine. Drug cultivation and production often take place in difficult-to-access areas that are controlled by non-state armed actors and militias linked to the Myanmar Army. The trading and consumption of drugs has become more visible in NSS since the military coup of February 2021, due to corruption, a lack of effective law enforcement, the ongoing civil war and the scaling back of already limited harm reduction programmes.

In this Working Paper, Kathy Win reports on research which set out to understand the role of CSOs, faith-based groups and EAOs in harm reduction programmes and to assess the challenges and opportunities surrounding attempts to respond to drug issues in Northern Shan State.

The paper explores the role of CSOs in providing harm reduction services, focusing on usage and access to harm reduction; the role of harm reduction programmes led by CSOs, faith actors and EAOs; the extent to which there is collaboration between different actors; and the challenges that face efforts to improve harm reduction and community resilience to drug harms.

Precarious lives, precarious treatments: Making drug treatment work in Northern Myanmar

In this Medical Anthropology article, Tim Rhodes, Khine Wut Yee Kyaw and Magdalena Harris explore how precarious livelihoods intersect with precarious treatments for heroin dependency in a setting affected by longstanding conflicts and an illicit drug economy as well as by recent events of pandemic and political change.

Working with 33 qualitative interviews with people who inject drugs in Kachin State, northern Myanmar, they explore how drug dependency treatment, especially methadone substitution, is made to work in efforts to sustain everyday livelihoods.

The analysis attends to the work that is done to enable therapeutic trajectories to emerge as “generous constraints” in precarity, and traces methadone substitution as an emergent intervention of livelihood survival.

Non-medical pathways away from harmful drug use in Kachin state, Myanmar

This Working Paper, by Mandy Sadan, engages with the need to diversify the parameters of analysis for the ‘drugs problem’ in Myanmar. The intention is to encourage more integrated and holistic approaches to these problems; to see them at different scales; and to put local experiences at the centre. This report focuses on an extended life-story narrative as a vehicle for our understanding.

The first part of the report discusses how taking an intersectional approach to understanding pathways out of harmful drug use may facilitate a more granular understanding of these issues, helping us to move away from a reliance upon homogenising representations and over-generalised experiences. It considers the potential value of ‘recovery capital’ frameworks for supporting long-term, sustained behaviour change among people who use drugs in this region and who wish to move away from harmful behaviours.

The second part of the report presents the life of the well-known singer and activist Nding Ah Ja, who tirelessly supports people who use drugs in the Kachin region. Nding Ah Ja is a significant local actor who works with people who use drugs and their families, especially those who have been incarcerated. He is a well-known and respected authority on these issues in the Kachin region, with authenticity as an advocate for the better treatment and support of people who use drugs and their families.

The conclusion discusses how a ‘life story’ approach enriches our understanding not only of the individual but also of the structural context of their life choices. Specifically, this is of great help in understanding the practical support structures that best help individuals who have to manage complex forms of discrimination or exist in settings of marginalisation.

Seminar series: Illicit Economies, Violence and Development

The Centre for the Study of Illicit Economies, Violence and Development (CIVAD) at SOAS, and the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), are organising a series of six seminars which will bring together academics, students, policy makers and practitioners with an interest and engagement in questions of illicit economies, violence and development.

Seminar 1: Frontiers, illicit flows and the geographies of uneven development (online)

This opening seminar discussed how the circulation of illicit flows (capital, commodities, people, ideas) shape and connect processes of (uneven) development within and across regions. Rethinking what is meant by key terms, it will took a systemic and structural look at how the world is changing, setting the agenda for the rest of the series.

Chair: Jonathan Goodhand (SOAS University of London)

Panelists: Michael Watts (University of California, Berkeley) and Dolly Kikon (University of Melbourne)

Date: 20th October 2022, 17:30-19.00 (GMT+01:00)

Watch a recording of the seminar here.

Seminar 2: Illicit economies, violence(s) and state formation in Latin America (online)

Chair: Jeff Garmany (University of Melbourne)

Speaker: Jenny Pearce (London School of Economics)

Date: 10th November 2022, 17:30-19.00 (GMT)

Venue: Zoom

Watch a recording of the seminar here.

Seminar 3: The everyday life of drugs: producers, dealers, consumers, enforcers (in-person)

This session, held in-person in London, showcased research on the everyday realities, perspectives and experiences of participants in illicit drug economies, and discussed the wider implications of everyday perspectives on drugs. How can the narrative frame around drugs shift to bring everyday life to the centre?

Chair: Maziyar Ghiabi (University of Exeter)

Panelists: Frances Thomson (University of Bradford); Neil Carrier (University of Bristol)

Discussant: Niamh Eastwood (Executive Director, Release)

Date: 8th December 2022, 17.30-20.00 (GMT)

Venue: SOAS – Brunei Gallery Lecture Theatre

Watch a recording of the seminar here.

Seminar 4: Militias, coercive brokers and public authority (online)

This seminar explores the entanglements between para state armed groups (PAGs) illicit economies, organised crimes and formal politics. It challenges dominant narratives on PAGs, which see them as a temporary response to governance deficits, or as automatically apolitical and criminal actors. It discusses the role of PAGs as an embedded feature of many frontier regions, in which they act as ‘coercive brokers’ who mediate between different actors, scales and jurisdictions.

Chair: Jenny Pearce (London School of Economics)

Panelists: Francisco Gutiérrez Sanín (National University of Colombia) and Antonio Giustozzi (RUSI)

Date: 12th January 2023, 17.30-19.00 (GMT)

Venue: Zoom

Watch a recording of the seminar here.

Seminar 5: Creating and implementing financial disruption strategies – successes and challenges. A UNODC perspective (online)

Chair: Heather Marquette (University of Birmingham and FCDO)

Speaker: Oliver Gadney (UNODC Global Programme Against Money Laundering)

Date: 7th February 2023, 17.30-19.00 (GMT)

Venue: Zoom

Watch a recording of the seminar here.

Seminar 6: Terrorism and illicit finance (online)

In 2019, the Security Council passed Resolution 2482, expressing ‘concern that terrorists can benefit from organized crime … as a source of financing or logistical support’. The resolution stressed the urgent need for research on the interlinkages that may exist between terrorism, organised crime and illicit finance. This reflected the growing international focus on the crime-terror nexus. This session will explore this nexus in practice including top-down responses alongside local efforts that harness local knowledge, local researchers and civil society.

Chair: Emily Winterbotham (RUSI)

Panel: Dr. Hans-Jakob Schindler (Counter Extremism Project); Dr. Keith Ditcham (Organised Crime and Policing, RUSI)

Date: 9th March 2023

Venue: Zoom

Watch a recording of the seminar here.

We eradicated coca: now what?

This year, Colombia commemorates five years since the signing of the Peace Agreement by the Colombian state and the FARC. It has also been almost five years that the families, who signed up to the PNIS (the coca crop substitution programme that came out of the Peace Agreement), have been waiting for the state to deliver what was promised to them after they voluntarily eradicated their coca bushes.

This digital report highlights the personal experience of some of these “substitution farmers”; these people who believed in peace, who got rid of their illicit crops and who, today, are suffering as a result of the state’s failure to fulfil the agreement.

Voices from the borderlands 2022

Voices from the borderlands 2022 – Life stories from the drug- and conflict-affected borderlands of Afghanistan, Colombia and Myanmar presents voices and perspectives from seven borderland regions.

This collection of life stories, gathered during our four-year research partnership, is intended for a broad audience of researchers, practitioners and policymakers working on issues related to drugs, development and peacebuilding.

The stories offer valuable insights into how illicit drugs, violence and conflict, poverty and development, and insecurity and resilience are entangled in the everyday lives of people in the borderlands. Our hope is that they challenge our readers to think about and engage more critically with how illicit drugs, development and peacebuilding interconnect in their work.

Agribusiness meets alternative development: Lessons for Afghanistan’s licit and illicit commodity markets

This AREU Research Paper, by Adam Pain, Mohammad Hassan Wafaey, Gulsom Mirzada, Khalid Behzad and Mujib Azizi, is a programmatic case study of the Afghanistan Comprehensive Agriculture and Rural Development Facility (CARD-F), a two-phase, aid-funded rural development programme (2009-2018). CARD-F’s design and first phase had counter-narcotics goals, which were less prominent in the agribusiness-focused second phase.

This research takes an ethnographic approach to understanding how different actors who were involved in the project viewed its activities and effects, and judged its outcomes. It considers what this reveals about the rationale of the project, and its effects on drug economies and processes of development in Afghanistan.